Physicists have caught ghostly particles called neutrinos misbehaving at an Illinois experiment, suggesting an extra species of neutrino exists. If borne out, the findings would be nothing short of revolutionary, introducing a new fundamental particle to the lexicon of physics that might even help explain the mystery of dark matter.

Undeterred by the fact that no one agrees on what the observations actually mean, experts gathered at a neutrino conference in June in Germany excitedly discussed these and other far-reaching implications.

Neutrinos are confusing to begin with. Formed long ago in the universe’s first moments and today in the hearts of stars and the cores of nuclear reactors, the miniscule particles travel at nearly the speed of light, and scarcely interact with anything else; billions pass harmlessly through your body each day, and a typical neutrino could traverse a layer of lead a light-year thick unscathed. Ever since their discovery in the mid–20th century, neutrinos were predicted to weigh nothing at all, but experiments in the 1990s showed they do have some mass—although physicists still do not know exactly how much. Stranger still, they come in three known varieties, or flavors—electron neutrinos, muon neutrinos and tau neutrinos—and, most bizarrely, can transform from one flavor to another. Because of these oddities and others, many physicists have been betting on neutrinos to open the door to the next frontier in physics.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

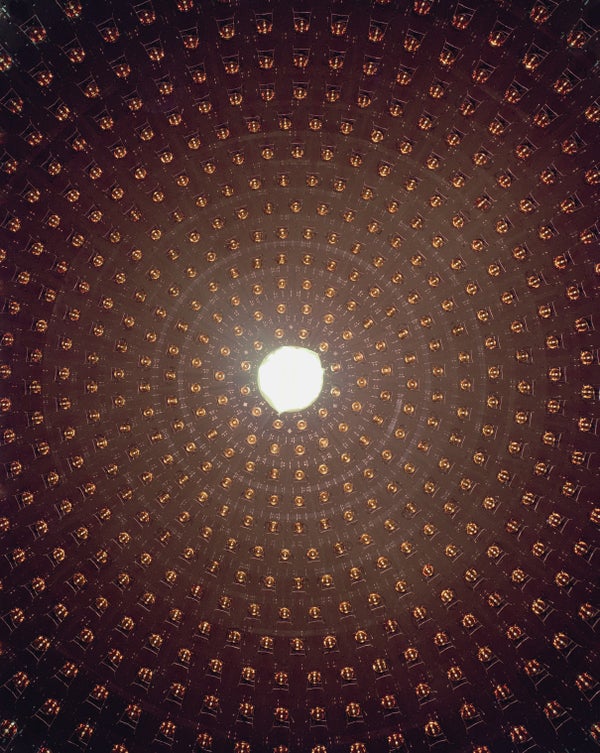

Now some think the door has cracked ajar. The discovery comes from 15 years’ worth of data gathered by the Mini Booster Neutrino Experiment (MiniBooNE) at Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Ill. MiniBooNE detects and characterizes neutrinos by the flashes of light they occasionally create when they strike atomic nuclei in a giant vat filled with 800 tons of pure mineral oil. Its design is similar to that of an earlier project, the Liquid Scintillator Neutrino Detector (LSND) at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. In the 1990s LSND observed a curious anomaly, a greater-than-expected number of electron neutrinos in a beam of particles that started out as muon neutrinos; MiniBooNE has now seen the same thing, in a neutrino beam generated by one of Fermilab’s particle accelerators.

Because muon neutrinos could not have transformed directly into electron flavor over the short distance of the LSND experiment, theorists at the time proposed that some of the particles were oscillating into a fourth flavor—a “sterile neutrino”—and then turning into electron neutrinos, producing the mysterious excess. Although the possibility was tantalizing, many physicists assumed the findings were a fluke, caused by some mundane error particular to LSND. But now that MiniBooNE has observed the very same pattern, scientists are being forced to reckon with potentially more profound causes for the phenomenon. “Now you have to really say you have two experiments seeing the same physics effect, so there must be something fundamental going on,” says MiniBooNE co-spokesperson Richard Van de Water of Los Alamos. “People can’t ignore this anymore.”

The MiniBooNE team submitted its findings on May 30 to the preprint server arXiv, and presented them in June at the XXVIII International Conference on Neutrino Physics and Astrophysics in Heidelberg, Germany.

A Fourth Flavor

Sterile neutrinos are an exciting prospect, but outside experts say it is too early to conclude such particles are behind the observations. “If it is sterile neutrinos, it’d be revolutionary,” says Mark Thomson, a neutrino physicist and chief executive of the U.K.’s Science and Technology Facilities Council who was not part of the research. “But that’s a big ‘if.’”

This new flavor would be called “sterile” because the particles would not feel any of the forces of nature, save for gravity, which would effectively block off communication with the rest of the particle world. Even so, they would still have mass, potentially making them an attractive explanation for the mysterious “dark matter” that seems to contribute additional mass to galaxies and galaxy clusters. “If there is a sterile neutrino, it’s not just some extra particle hanging out there, but maybe some messenger to the universe’s ‘dark sector,’” Van de Water says. “That’s why this is really exciting.” Yet the sterile neutrinos that might be showing up at MiniBooNE seem to be too light to account for dark matter themselves—rather they might be the first vanguard of a whole group of sterile neutrinos of various masses. “Once there is one [sterile neutrino], it begs the question: How many?” says Kevork Abazajian, a theoretical physicist at the University of California, Irvine. “They could participate in oscillations and be dark matter.”

The findings are hard to interpret, however, because if neutrinos are transforming into sterile neutrinos in MiniBooNE, then scientists would expect to measure not just the appearance of extra electron neutrinos, but a corresponding disappearance of the muon neutrinos they started out as, balanced like two sides of an equation. Yet MiniBooNE and other experiments do not see such a disappearance. “That’s a problem, but it’s not a huge problem,” says theoretical physicist André de Gouvêa of Fermilab. “The reason this is not slam-dunk evidence against the sterile neutrino hypothesis is that [detecting] disappearance is very hard. You have to know exactly how much you had at the beginning, and that’s a challenge.”

Another Mystery?

Or perhaps MiniBooNE has discovered something big, but not sterile neutrinos. Maybe some other new aspect of the universe is responsible for the unexpected pattern of particles in the experiment’s beam. “Right now people are thinking about whether there are other new phenomena out there that could resolve this ambiguity,” de Gouvêa says. “Maybe the neutrinos have some new force that we haven’t thought about, or maybe the neutrinos decay in some funny way. It kind of feels like we haven’t hit the right hypothesis yet.”

Unusually, this is one mystery physicists will not have to wait too long to solve. Another experiment at Fermilab called MicroBooNE was designed to follow MiniBooNE and will be able to study the excess more closely. One drawback of MiniBooNE is that it cannot be sure the flashes of light it sees are truly coming from neutrinos—it is possible that some unknown process is producing an excess of photons that mimic the neutrino signal. MicroBooNE, which should deliver its first data later this year, can distinguish between neutrino signals and impostors. If the signal turns out to be an excess of ordinary photons, rather than electron neutrinos, then all bets are off. “We don’t know what would do that in terms of physics, but if it is due to photons, we know that this sterile neutrino interpretation is not correct,” de Gouvêa says.

In addition to MicroBooNE, Fermilab is building two other detectors to sit on the same beam of neutrinos and work in concert to study the neutrino oscillations going on there. Known collectively as the Short-Baseline Neutrino Program, the new system should be up and running by 2020 and could deliver definitive data in the early part of that decade, says Steve Brice, head of Fermilab’s Neutrino Division.

Until then physicists will continue to debate the mysteries of neutrinos—a field that is growing in size and excitement every year. The meeting in Heidelberg, for example, was the largest neutrino conference ever. “It’s been a steady ramp-up over the last decade,” Brice says. “It’s an area that’s hard to study, but it’s proving to be a very fruitful field for physics.”