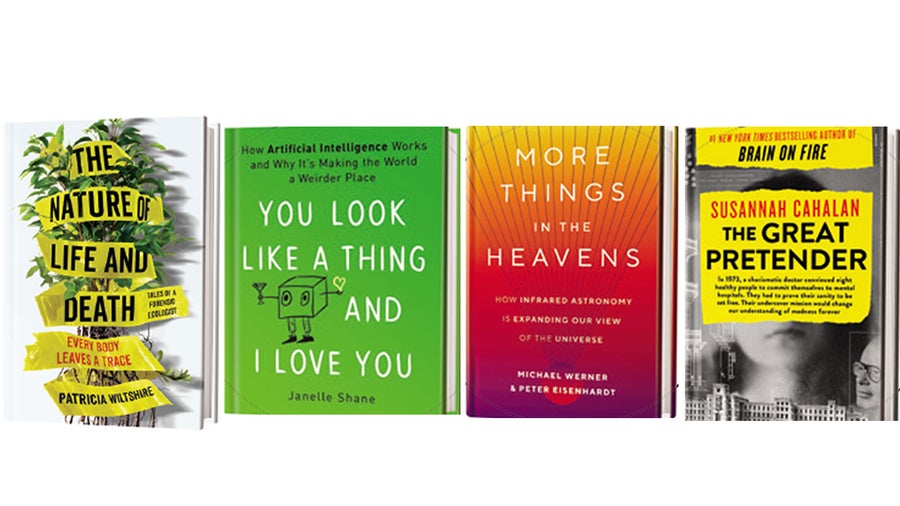

The Nature of Life and Death: Every Body Leaves a Trace

by Patricia Wiltshire

Putnam, 2019 ($27)

For many, pollen is a nuisance, responsible only for sniffles and sneezes. For forensic ecologist Wiltshire, pollen is a portal, transporting her to the scene of a crime. Microscopic pollen particles that cling to a suspect's jacket or a victim's hair can reveal critical clues about a crime scene's ecosystem. Using this evidence, Wiltshire can often re-create, in brilliant detail, where a victim spent his or her final moments—often to the surprise of the detectives working with her. Between gripping case studies, Wiltshire weaves in charming tales from her childhood in Wales and hard-won lessons on navigating the male-dominated fields of science and law enforcement.—Jennifer Leman

You Look Like a Thing and I Love You: How Artificial Intelligence Works and Why It's Making the World a Weirder Place

by Janelle Shane

Voracious Books/Little, Brown, 2019 ($28)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Training an AI to write pickup lines—the source of this book's title—might sound frivolous, but the process can illuminate the often opaque inner workings of these computer constructs. Shane is an optics researcher who also explores the strange creations of AI systems on her blog, and here she brings an analytical eye to explain how AIs operate, what problems they can solve, and what will likely remain too hard, or too dangerous, for them to tackle. The programs tend to carry over and enhance bias from data they are given, for instance, and their black box nature makes it difficult to catch errors and misinterpreted goals. Shane's humorous but weighty discussion reveals the promise and peril of an AI future.—Sarah Lewin Frasier

More Things in the Heavens: How Infrared Astronomy Is Expanding Our View of the Universe

by Michael Werner and Peter Eisenhardt

Princeton University Press, 2019 ($35)

Infrared light falls to the right of visible light on the electromagnetic spectrum, with longer wavelengths than what the eye can see. And because the expansion of the universe stretches the wavelength of light from distant objects, many of the farthest, oldest things in the cosmos are visible only in infrared. The best tool astronomers have for seeing the infrared universe is the Spitzer Space Telescope. Launched in 2003, it has glimpsed galaxies, planets, asteroids, and, especially, “the youngest, most distant galaxies yet discovered,” write Spitzer scientists Werner and Eisenhardt. Now, before the telescope shuts down in January 2020, the authors recount the major sights that greeted Spitzer's infrared eyes on the skies.—Clara Moskowitz

The Great Pretender: The Undercover Mission That Changed Our Understanding of Madness

by Susannah Cahalan

Grand Central Publishing, 2019 ($28)

In a famed experiment, psychologist David Rosenhan and seven other “pseudopatients” faked their way into psychiatric hospitals, claiming to hear voices. He subsequently published a 1973 paper in Science detailing how hospital staff pathologized normal behavior, mistreated patients and kept the pseudopatients institutionalized for weeks. The paper caused an uproar and confirmed widespread mistrust of the mental health system. Although Rosenhan's work influenced the future of psychiatric care in the U.S., his paper did not tell the whole story. Writer Cahalan digs deeper—starting with the charismatic Rosenhan and his mysteriously unfinished book about the experiment. In her quest to track down the facts, Cahalan discovers that some of Rosenhan's claims were, at best, overstated and may have been completely untrue.—Leila Sloman